The simple answer is, maybe. Called by various names, a short lingual frenulum, ankyloglossia, or tongue tie… we require an assessment of tongue mobility during every one of our new client speech evaluations. Often we get a referral for a child who sounds correct, and do score within “normal limits” on a standardized speech assessment, but when we assess how the child is using their tongue, jaw, lips and cheeks to produce speech sounds we find that there are compensatory movements which they have developed to make them “sound clear” to all. Because of this, these children do not qualify for speech in school. They have self-learned, these compensatory movements in order to help them “sound clear” to others and unfortunately, they can lead to shifting of the jaw and displacement of teeth.

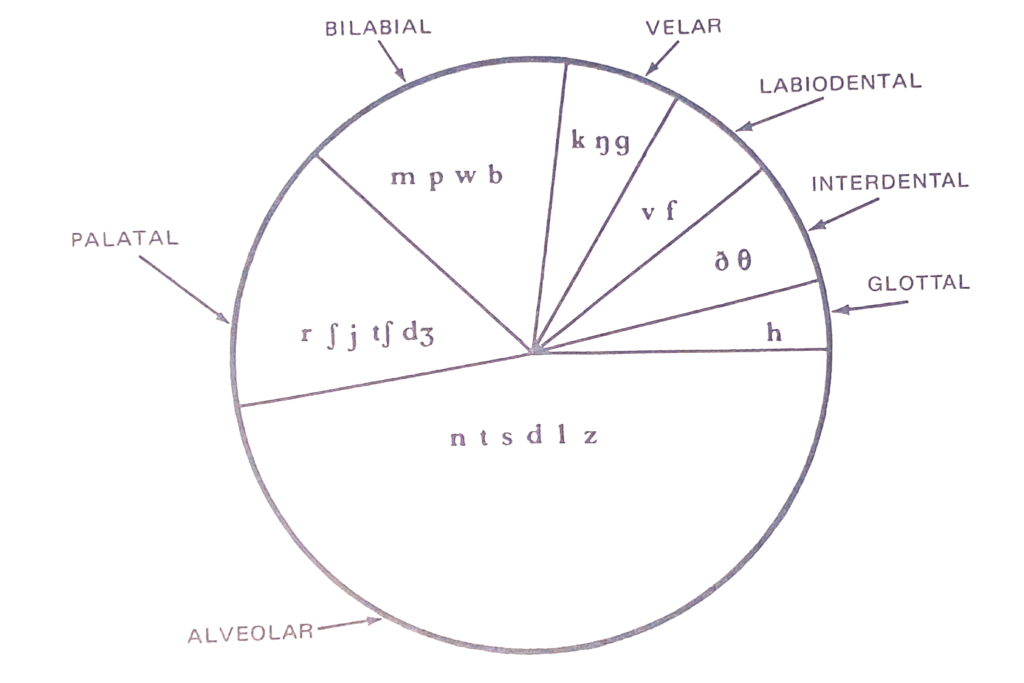

There are a series of tests which use to determine how severe the tie impacts a child’s speech. In looking at speech sounds in isolation we can break apart areas where we see patterns of errors. American English is broken down into categories based on where the sound is produced in the mouth. For example, all of the alveolar sounds (L,T,D,Z,S,N) are all produced in the same place in the mouth. You produce them with the tongue tip up, on the little ridges behind your front teeth. If you are not able to stablize your jaw and get your tongue tip up, those sounds will sound distorted. We often see these sounds are distorted in most cases. These sounds are also the most common sounds in English. Though, these are often seen the most, we also see kids with distortion in palatal, interdental and velar sounds. See image for detail.

It would be uncommon to see errors in bilabials, but often children who have poor resting posture of their tongue and whose tongue is often pushed forward in their mouth will also have errors in the productions of the bilabials.

What we know now about tongue tie is that the long term effects of a tongue tie lead to greater health issues. A short lingual frenulum modifies the position of the tongue in the mouth in childhood, and impairs oral and facial development potentially leading to sleep apnea throughout a child’s life (Huang et. al 2015). Therefore we suggest that a whole team approach weighs in on the severity and impact of the tongue tie and how it effects the child overall, and not just in one area.